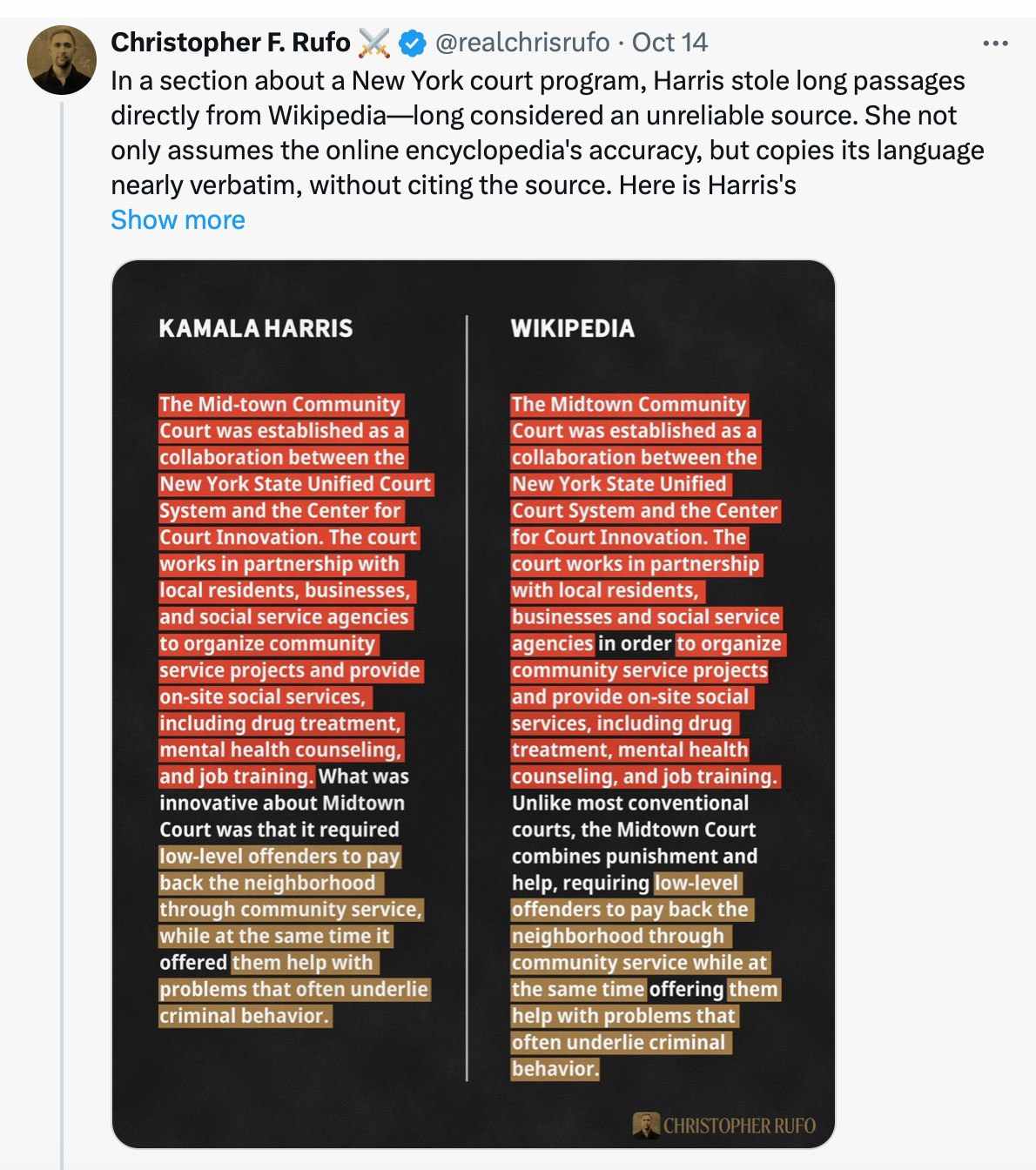

This week brought a piece of minor campaign news: Kamala Harris has been accused by conservative activist Christopher Rufo of plagiarizing passages from her 2009 book Smart on Crime. (Whatever you think of Rufo’s aims, you’ve got to admire his hustle; he's been enormously effective at generating news and influencing policy debates.)

I don’t care much for this new trend of using technology to scrutinize the writing of famous figures. I assume this will be a passing fad that we will one day look back on with some befuddlement, like the controversies that used to erupt around whether candidates smoked marijuana in college.

The plagiarism accusation against Harris seems like pretty small beer to me — errors of citation, maybe, but hardly deliberate theft of someone’s ideas. I agree with John McWhorter’s argument that using the same word, “plagiarism,” to describe both of these transgressions invites confusion — people who have committed misdemeanors end up getting branded as felons.

I was modestly surprised that the New York Times decided to write about the story. Although the way things go these days, the Times was then attacked by conservative media outlets for not taking the accusations seriously enough. Sigh. Perhaps this is a good time to underline the argument I have made in the past: we are suffering from an excess of media criticism and it is not making the media perform any better. Personally, I think the whole plagiarism issue should have a half life measured in minutes, not days.

But, at the risk of continuing the discussion, I am writing this because one of the passages that Harris allegedly plagiarized in her book was about a project that I worked on when I was the director of the Center for Court Innovation: the Midtown Community Court. Here is a selection:

Chanelling the spirit of Pollyanna, I hope that this whole controversy will drive people to actually consider the substance of Harris’ book. When she was the District Attorney in San Francisco, Harris was not one of those “progressive prosecutors” who is essentially a defense attorney in disguise. But she was hardly an old-school, lock-’em-all-up, law-and-order type either. Instead, she was a sensible liberal who sought to use the justice system to respond to criminal behavior, but who leavened her approach to justice with mercy.

Harris’ support of a San Francisco community justice center, inspired by the Midtown model, was consistent with this philosophy. As she details in Smart on Crime:

Our Tenderloin District has long been a crime-ridden area. Within its borders is drug dealing, prostitution, and a large number of young children who are neglected and exposed to crime. Historically, a police officer who sees someone breaking into a car would arrest the offender, who later would be released and told to come back to court on a future date. The problem was, too many never made it back to court.

Why? Many people who are living on the streets there are suffering from addiction and mental illness but are receiving no treatment. Turning a blind eye dooms a lot of individuals and turns the neighborhood into a dangerous, dirty, crime-ridden zone. Our Community Justice Center is a collaborative, problem-solving center with a court on site, designed to provide accountability for lower level criminal behavior and at the same time to address the root issues associated with this behavior, such as substance abuse, mental illness, and lack of shelter. The center is based on the principle of immediacy — immediacy of consequences and immediacy of services. The key is having everything under one roof: criminal justice agencies, service providers, and members of the bench. It’s a simple but effective model.

I’m biased, of course, but this kind of approach to crime — combining punishment and help to forge sanctions that offer defendants a pathway to rehabilitation — seems like a sensible middle path that reflects both conservative insight (crime should have consequences) and progressive wisdom (people are often led to criminal behavior by circumstances in their life).

Last year, Matt Yglesias went back and read Smart on Crime. He offered this description of Harris’ tenure as DA:

She’s comfortable calling for more resources on multiple fronts simultaneously — more rehabilitative programming in prisons, more re-entry support, more police on the streets, more shot-spotter and other surveillance technology, more witness protection, more victim services. She’s also “smart” in the sense that as a law enforcement practitioner, she is aware that you need to operate within a budget constraint and that “just make the sentences longer” is often not the cost-effective choice.

Yglesias concludes by arguing that Harris should re-read her own book and tap into these ideas again. I imagine that re-reading Smart on Crime is probably the last thing that she wants to do right now given the current controversy, but I think that is still good advice. Harris’ approach to crime made sense back then, and I think it still does today.