A few months ago, I wrote a piece for The Good Men Project extolling the virtues of the classic western Rio Bravo. My basic argument was that even as we critique westerns for racism, sexism and a myriad of other violations of contemporary mores, we should hold on to what was great about them. In the case of Rio Bravo, this means recognizing that the film advances a set of positive personal values, including accountability, professionalism, and sacrifice for the common good.

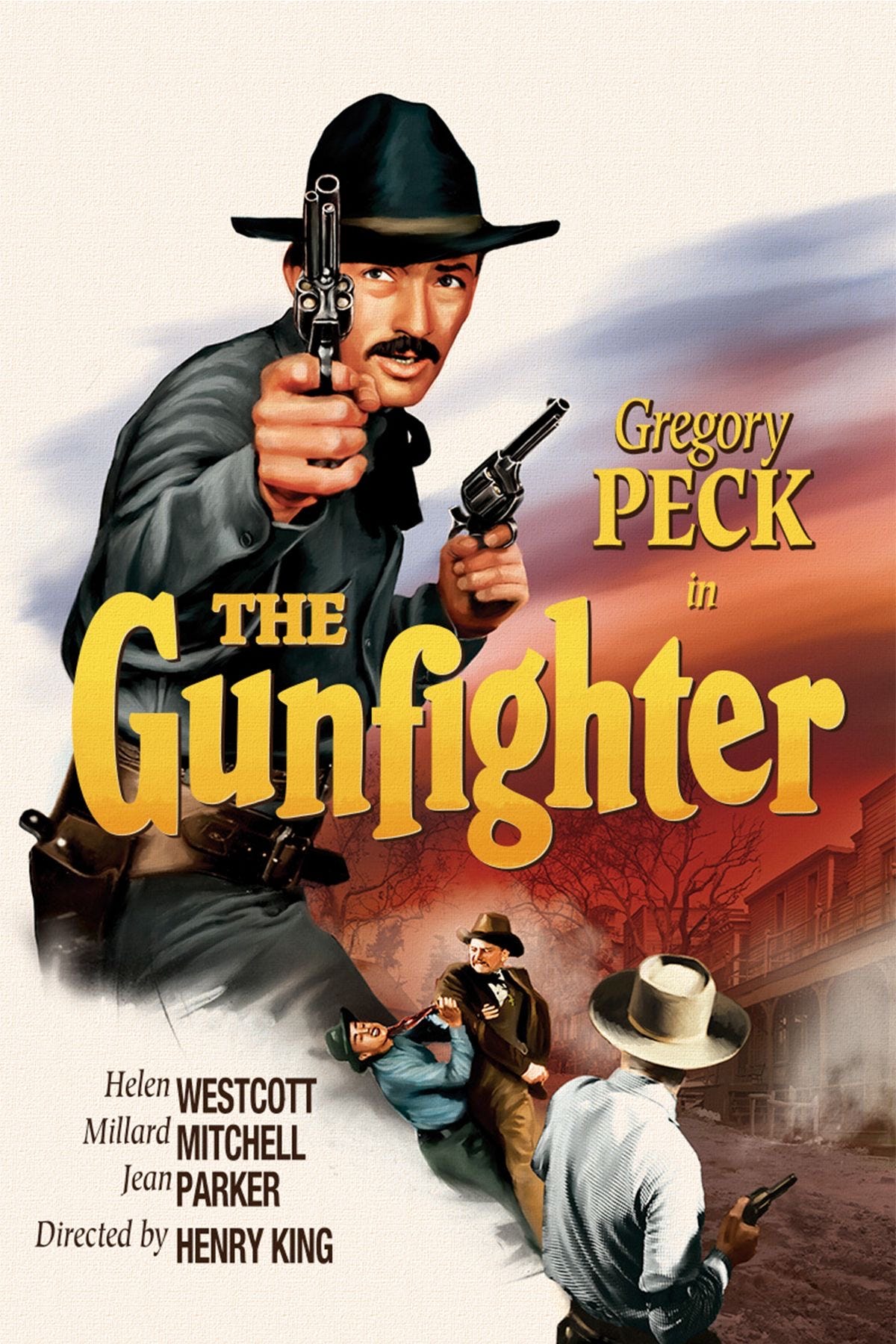

I enjoyed Rio Bravo so much that I decided to go back and re-watch some of my favorite Westerns — and to catch a few that I had previously missed. So over the past couple of months, I have watched Once Upon a Time in the West, Red River, The Gunfighter, The Big Country, Shane, Vera Cruz, Johnny Guitar, Gunfight at the OK Corral and a few others.

My (virtual) companion for this tour of the western was an old college professor of mine, Richard Slotkin. Indeed, it was taking classes with Slotkin that sparked my interest in the western in the first place. For anyone with an interest in the topic, I can’t recommend highly enough this collection of lectures by Slotkin for a class that he taught entitled Western Movies: Myth, Ideology & Genre. I listened to several of these lectures and they really enhanced my enjoyment, particularly when the film in question wasn’t so great (I’m looking at you, Vera Cruz).

As Slotkin and others have explained, the basic outlines of the western genre are simple: somewhere on the frontier of the American west, a heroic individual (almost always a white man) must use violence against the forces of lawlessness (sometimes, but not always, embodied by Native Americans) in order to advance civilization.

This kind of narrative used to strike a deep chord for the American public. Between 1940 and 1960, Hollywood released up to 140 westerns per year. (And this almost certainly underplays the public appetite for the genre, since it doesn’t include TV or radio westerns.)

But interest in the western has dried up in recent years. According to The Atlantic, only 142 westerns were released across the entire decade of the 2000s. I’d be surprised if the 2020s even produces that many.

I’m not exactly sure why westerns have fallen out of favor but it seems to me that a big reason is where I started my Rio Bravo piece: many people have understandably come to feel uncomfortable with some of the political messages that are often contained in the genre, including not just how westerns approach issues of race and sex but also violence, capitalism, and the idea of American manifest destiny.

I do think these are fair critiques — some westerns really are tough to watch these days. But what struck me as I did my little dive into the genre was that the political criticisms of the western are clearly not a new phenomenon. Indeed, many of the classic westerns were palpably wrestling with these critiques more than a half century ago. Just a few examples:

Despite its name, The Gunfighter (1950) does not build up to a climactic showdown between the titular hero and his adversaries. Instead, the film is a rumination on the wages of celebrity and the dark side of violence. Johnny Ringo (played by Gregory Peck) is forever trapped by his violent reputation, worn down by the need for constant vigilance against potential challengers and doomed to be hounded out of every town he visits.

The Big Country (1958) is a classic example of Hollywood attempting to have its cake and eat it too — it is ostensibly a pacifist film but it still manages to deliver plenty of shootings and fistfights along the way. Still, the film fundamentally makes the case that using violence to resolve disputes is wrong. It also raises important questions about traditional notions of masculinity, pointing to the absurdity of overvaluing the importance of saving face in all situations.

Red River (1948) is the story of Thomas Dunson, a cattle rancher who decides to settle in Texas. Dunson is played by arguably the most important western star (John Wayne) and evinces many of the qualities of the archetypal western hero (courage, determination, skill with a gun). But while the ending partially (and bizarrely) redeems Dunson, throughout most of the film it is clear that Dunson is a remorseless monster, driven by avarice and megalomania to brutalize friend and foe alike.

The Paleface (1922) is not technically a classic western, but rather a silent comedy starring Buster Keaton. (I have also been bingeing a lot of Buster Keaton of late.) Still, I mention it here because, even in a film with plenty of objectionable elements (including multiple white actors donning “redface”), the plot is set in motion by a frank depiction of white American capitalists ruthlessly stealing land from American Indians.

My point here is not to absolve the western of all sins, but rather to make the case that these old films are richer and more complex than they might appear at first glance. Many of the best westerns are essentially revisionist westerns that seek to interrogate the genre and its values from within. Here’s hoping that Hollywood sees fit to make more of them.