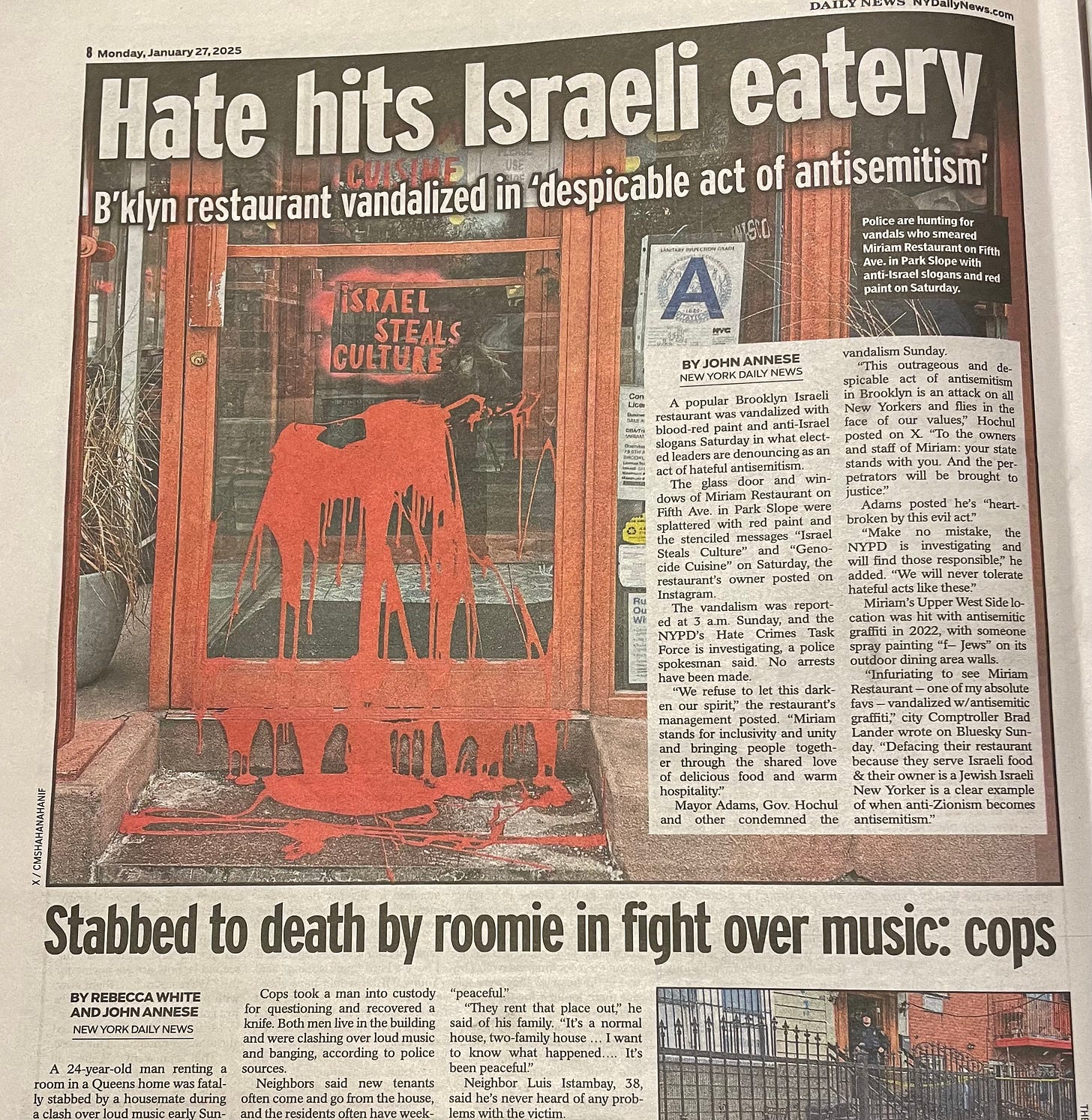

This past weekend, Miriam, an Israeli restaurant located around the corner from me in Brooklyn, was hit with graffiti. In blood-red stencils sprayed on its front door and windows, the restaurant was accused of “stealing culture” and engaging in “genocide cuisine.”

The denunciations came thick and fast. New York City Mayor Eric Adams called it a “despicable act of antisemitism.” City Comptroller Brad Lander, who I once bumped into eating at Miriam, said the graffiti was “a clear example of when anti-Zionism becomes antisemitism.” Congressman Ritchie Torres stopped by in person to show support for the restaurant and its Israeli owner, Rafael Hasid. Even City Councilwoman Shahana Hanif, a prominent local voice for the Palestinian cause, condemned the graffiti, labelling it “an act of hate.”

Like these politicians, I find the vandalism of Miriam deplorable. The graffiti is obviously an impediment to the healthy functioning of a local business, which must bear the costs of clean-up and the aggravation of unwanted media attention.

More than this, the vandalism violates the spirit of live-and-let-live civility that is essential to thriving urban life in a diverse city. The message that is sent to Jews in Brooklyn is chilling: You are being watched and this could happen to you.

It is notable that in the past year or so of walking around Brooklyn, I have seen precious few public displays of support for Israel, despite the fact that roughly one out of four Brooklynites is Jewish. (“Ceasefire Now” posters and pro-Palestinian graffiti are prominent throughout the borough.) Perhaps Jewish Brooklynites have already come to the conclusion that discretion is the better part of valor. After all, this week was not the first time a prominent local Jew has been targeted with graffiti – six months ago, the director of the Brooklyn Museum also had her home defaced.

Many left-wing activists view this kind of vandalism as a legitimate form of protest against the war in Gaza. On Twitter, Palestinian activist Nerdeen Kiswani, the founder of Within Our Lifetime, suggested that Miriam was a Zionist restaurant that profits off of “appropriated food.” She declared that the vandalism was not an act of hate: “Let’s not act like vandalism doesn’t belong in NYC—a city built on it. No one cares about random graffiti, yet this instance gets condemned?” One wonders what Kiswani’s response would be if Arab-owned businesses on Atlantic Avenue were targeted with graffiti suggesting they were complicit in terrorism. Would that also be an appropriate expression of grassroots organizing?

And yet, even though I am upset about what happened at Miriam, I also find myself wanting to pump the brakes on the non-stop coverage of the incident, which I fear may do as much harm as good.

In this era of social media outrage, countless minor local provocations are duly recorded and then sent out to the entire world for consumption and approbation (or celebration, as the case may be). But not every upsetting street protest augurs the coming of Kristallnacht. And not every instance of antisemitism is a step on a slippery slope that leads inexorably to the Holocaust.

According to Matt Yglesias, we are living through a time of “toxic self-involved drama” that threatens to make our problems worse through “twitchy overreaction.” The first week of the new Trump administration offers ample support for this theory of knee-jerk over-correction: Tightening control of the borders is one thing, attempting to eliminate birthright citizenship via executive order is quite another.

In an age of umbrage, one of the key challenges facing us all is calibration. Now, more than ever, we are confronted with so much to get upset about. How should we react? All too often these days, the answer is to immediately go on social media to register our indignation. But that just adds further fuel to the engines of online outrage which are perpetually winding all of us up to toxic levels of hysteria.

I must confess that my first instinct, when I heard what happened at Miriam, was to go on Twitter to vent my ire. But I decided to wait 24 hours instead. With the benefit of more time to think, I chose a different course: I made a plan with a Jewish friend to have lunch at Miriam this week. Is this doing enough to combat antisemitism? I don’t know. But to me it feels correctly calibrated to the scale of the offense.